Introduction

Cash flow forecasting is arguably the most important task in running a business. Any business — including yours! That’s why we’ve broken down cash flow budgeting, planning, and forecasting into a common-sense approach applicable to any business.

What do we mean by budgeting, planning, and forecasting in the context of cash flow?

- Planning — setting out the business’ intentions for a period of time; aka where we want to go.

- Forecasting — setting and updating expectations for a period of time, based on what we know and are anticipating; aka where we are going.

- Budgeting — breaking down the plan into financial years and months.

With all this in mind, let’s break it down and see how you can put business cash flow forecasting into practice.

Find your cash comfort level

Here’s a little test for you: login to your online bank account or grab your bank statement if you have it handy.

Look at the current balance. You know straight away whether you are comfortable with that amount — of course, we all want more cash, but there’ll be many reasons why you feel okay or not okay with this number

Comfortable: You’ve been in business for a long time, and you understand your industry well. Your future cash flow movements are predictable, your outflows are stable, and you have enough cash in reserve to overcome any short-term spikes or downturns.

Uncomfortable: You are new to your business and/or industry, the current environment is uncertain, or a sudden emergency has resulted in a cash drain and ongoing outflows of unknown quantities.

Managing your cash flow comfort level

Whatever your situation, it’s important to understand why you feel the way you do when you see your bank balance and what’s contributing to that feeling.

Some people purely operate on “gut feel”. While they may be able to sustain this for a while, it’s hard to optimise positive cash flow based on guessing versus facts.

So, how do you arrive at the minimum comfort level of cash you need available for your business to keep running?

Start with what you know — fixed costs and regular outflows

These are the cash outflows that occur regardless of anything else happening in your business, turning over in less than a 12-month period.

You must have the cash available at all times to cover these items. While most occur regularly, such as payroll, the ones that don’t can catch you out. Think about:

- Rent, insurance, utilities, and other creditors

- Payment terms of various suppliers

- Net pays, income tax, payroll tax, superannuation

- Income tax, GST/sales/value-added tax, property rates

Most of these transactions occur monthly or less frequently, but some, like annual insurance or workers’ compensation premiums, don’t. So, how do you work out what cash you need on hand at all times to cover these?

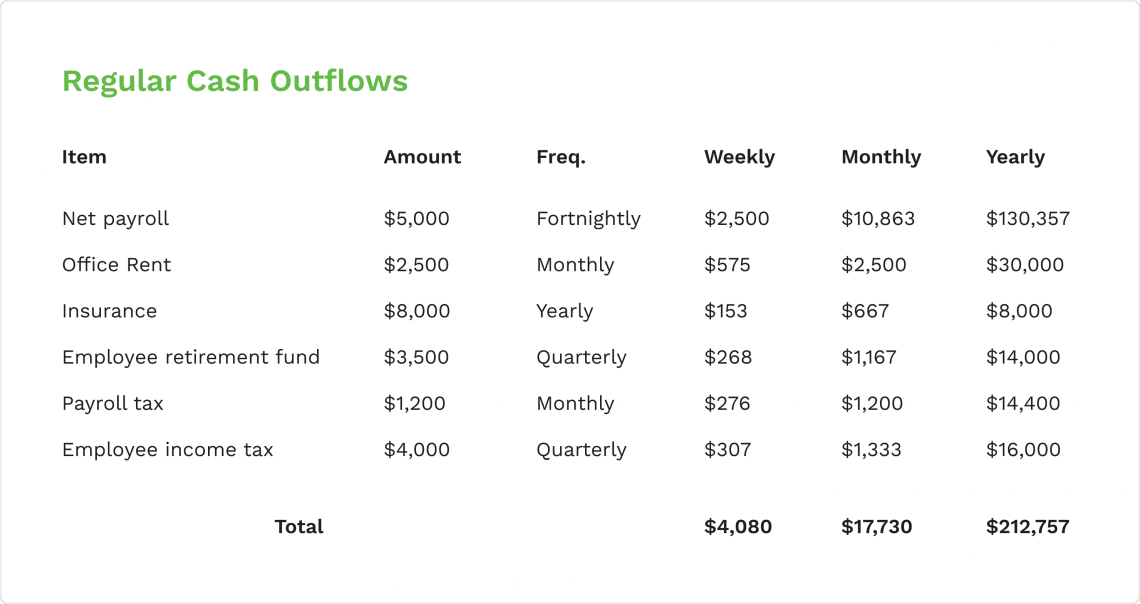

There are a couple of ways to approach this. To take a more conservative approach, start by working out the total cash outlay over 12 months, then work out what this looks like monthly, fortnightly or weekly — whatever timeframe you like to work with. Here’s a simple example:

A typical approach to determining a comfort level of cash is to take the monthly figure and make sure you have a certain number of months of this cash on hand for security.

Most people keep between two-to-six months’ of regular outflows on hand

The more confident you are about business conditions, the less cash you may need to keep on hand — and the opposite, too.

Short-term revenue inflows and variable costs

We’ve only looked at outflows so far, but you’re in business to make money — not just spend it! Forecasting inflows is never easy — whether we’re talking big business or small business cash flow forecasts. You can have customers that seem identical but are worlds apart when it comes to payment behaviour.

You need to factor in typical payment terms based on past behaviours, as well as allow for anticipated growth/contraction in sales. It’s better to be realistic with forecasting growth or the addition of new inflow streams.

The final thing to consider is variable costs linked to your inflows. These happen only when revenue-generating events occur.

An example would be delivery costs when distributing a sold item to a customer. If you sell an item for $100 but it costs $20 to deliver, you need to think about how many $80 transactions are going to occur.

Arriving at your cash comfort level

Once you’ve taken the above components of cash inflows into consideration, you may revise your comfort level of cash, given your confidence around inflows.

Many businesses don’t do this; some even operate covering payroll-related outflows only. It all depends on the level of risk you’re prepared to take and your confidence in your incoming cash flow.

Your comfort level may vary with seasonality, too. For example, a tourism-related business will have higher cash inflows during peak tourist times.

However you end up at your comfort level of cash, here’s the test: every time you look at your bank balance, you know within yourself if that’s the amount you need. If it’s too low, you need to take immediate action. If it exceeds your comfort level, put that excess cash to its best use — that’s what it’s there for!

Get to know your transactions

Transaction behaviours are simple to understand, but a lot of businesses ignore them, which leads to cash flow problems as their plans are based on budgeted profit and loss (P&L) statements.

This means their cash flow forecasting lacks the detail needed for an accurate picture, which can lead to the wrong decisions being made or even running out of cash.

Profit and loss statements are a good place to start but rarely do they give you an accurate cash flow forecast for daily or weekly usage. This is because budgeted P&L statements:

- Are prepared for a financial year only and the most detail is activity per calendar month.

- They exclude any items that aren’t strictly profit and loss items, like long-term transactions. If it’s cash, it belongs in your cash flow plan.

- They contain non-cash items, such as depreciation and leave accruals. If you transpose these to your cash flow plan, you’ll be overstating outflows.

Let’s examine some different transaction behaviours.

Frequency

Daily | Weekly | Fortnightly | Monthly | Quarterly |Half-Yearly | Yearly

All transactions have their own frequency and your cash flow plan needs to accurately reflect this.

For example, you may have an advertising campaign running for the entire financial year. As the campaign covers the whole year equally, it’s correct to distribute the expense equally across all months (or even weeks).

However, if you’re paying for that campaign in upfront quarterly instalments, these four cash outflows must be reflected in your cash flow plan — not the averaged monthly expense.

While you may start planning based on your profit and loss items, you must identify the frequencies at which your transactions actually occur in order to produce an accurate cash flow plan.

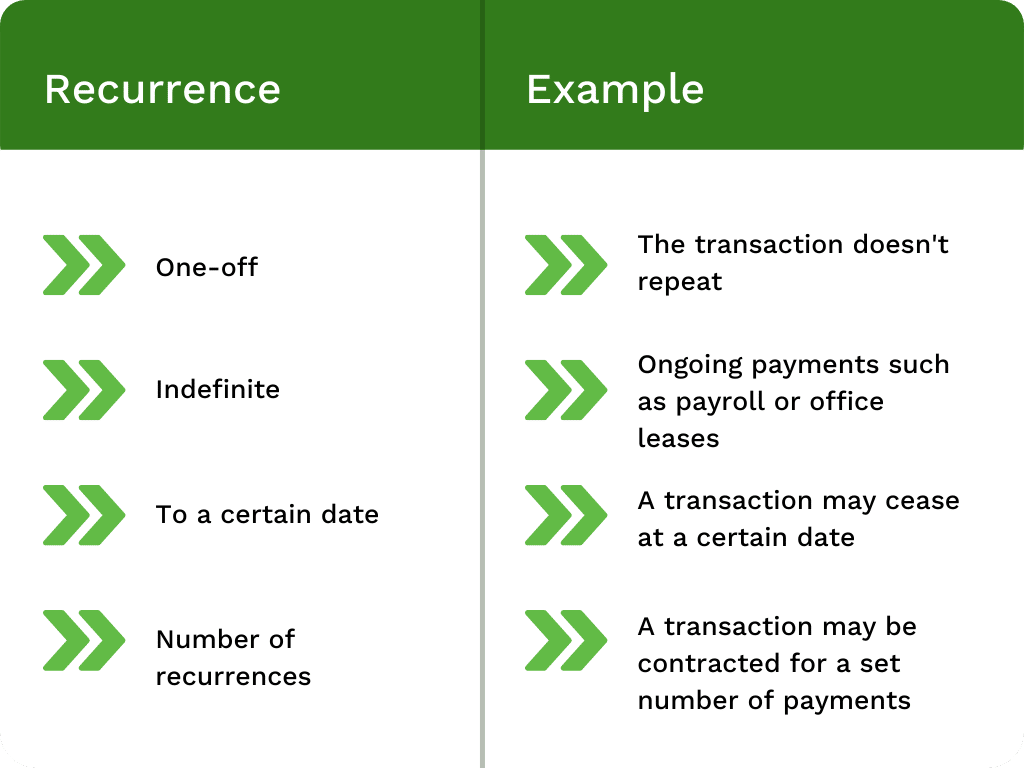

Recurrence

Not all transactions occur endlessly on a set frequency and you need to ensure your transactions are forecast with recurrence in mind.

If you take annual numbers for transactions and distribute them equally across each month (the correct treatment for accounting purposes), extrapolating this to cash flow movements may not be correct.

Keep in mind the start and end dates of transactions that may not span the entirety of your cash flow forecasting period (e.g. a 48-month lease that finishes in three months’ time), as well as inflation that applies periodically, often annually.

Timing

Even after considering frequencies and recurrences, the potential timing of cash movements can throw out your plan, especially when it comes to cash inflows.

You may know the payment behaviours of your customers, but this may change, perhaps due to seasonality or other issues in their business, which changes when you get paid.

You can never be certain about the payment behaviours of new customers, despite what assurances and credit reports say. Timing of transactions is crucial, so ensure you know the impacts of different scenarios, including customer payment behaviour and variable costs.

Long term

We’ve focused on short-term transactions and their behaviours, so now we’re in a position to understand our long-term transactions.

These are transactions that involve time spans of greater than 12 months, for example:

Short-term net cash flow impacts your long-term inflows, whether it’s buying or selling assets, taking on equity, servicing loans or expanding the business.

Set your forecast timeframe

Businesses that do not have a cash flow forecasting process are usually forced into short-term forecasting at the last minute.

But if cash flow is part of your business management process (and it should be), you’ll know you can avoid panic and stay in control. Let’s look at different forecasting timeframes.

Short-term timeframes

A short-term cash forecast should be reasonably accurate. Unless something completely unexpected happens, you should have a good understanding of your transactions.

For all short-term forecasts, you should have a daily cash balance available to you. A forecast giving you only weekly or monthly balances is not enough, particularly in times when actual cash flows are tight, as it hides larger peaks and troughs you need to be aware of.

Weekly, monthly, and quarterly — These timeframes let you stay on top of current, known, or expected events. Knowing movements on a daily basis is the best and most detailed way to plan cash flow.

Rolling 12-month forecasts — Most recurring short-term transactions have at most a 12-month cycle – annual income tax, workers’ compensation and insurance, for example — and a lot have a half-yearly or quarterly cycle, such as tax instalments.

With a rolling 12-month forecast, you’ll always have these transactions accounted for. You can’t afford to miss them!

If you do only one cash flow forecast in your business, it should be a rolling forecast

Payables and receivables — Consider payables and receivables on an individual basis where possible, looking at the impact of changes to expected payment/receipt dates.

Even for short-term forecasts, it’s good practice to work with a number of feasible scenarios. This is particularly the case when you’re relying on receipts from customers, and there’s uncertainty around when these will be received and in what amounts.

Long-term timeframes

While more speculative than short-term forecasts, long-term forecasts give you an idea of how long-term inflows and outflows can be used.

3-to-5 year forecasts — These long-term forecasts show when large transactions can take place (both cash surpluses and deficits), so you can prepare and make adjustments accordingly.

Scenarios for long-term forecasts can make cash balances vary wildly, so it’s essential all assumptions underpinning these scenarios are documented and understood.

Scenarios — The future is too uncertain to have only one view of it. You need to consider all feasible possibilities to ensure you have everything in place to deal with or take advantage of all kinds of scenarios.

At the very least, you should plan around “Expected”, “Best-Case” and “Worst-Case” scenarios, and know what factors influence these.

Start with your “Expected Case” (what you honestly think will happen and why) and use that plan as a basis for the other scenarios.

Business unit planning

It can be far easier to understand and forecast if you do it for each individual part or unit of your business. It’s common to do this for profit and loss budgeting and reporting, so there’s no reason to exclude this level of analysis from a cash flow perspective.

Depending on your business, this will mean breaking up your cash flow plans into projects, sites/stores, or operating divisions. You’ll then need to consolidate these unit plans into an overall plan to see the big picture.

Comparing to actuals

Just like comparing actual to budgeted profit and loss, you should do the same for cash flow. This will tell you the parts of your business with the biggest impact on cash flow, and those are the most susceptible to changing conditions.

Comparing actual cash flow to planned cash flow will tell you where you’re tracking well and where the gaps are. If there’s one thing you must stay on top of, it’s cash flow movements. No cash = no business! You are aiming for positive net cash flows.

Consider different scenarios

A common error made in business management is equating profit and cash. This is dangerous when it comes to actual cash flow and your comfort level.

Let’s take a simple cash flow forecast example and look at it under three different scenarios. Don’t worry — cash flow software makes all of this much easier on the eyes.

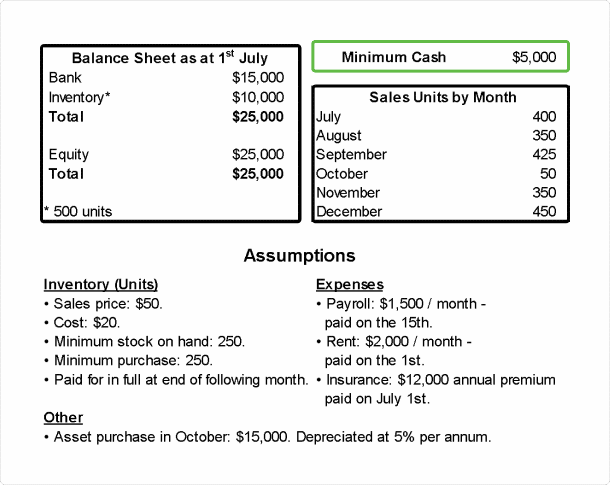

Example data

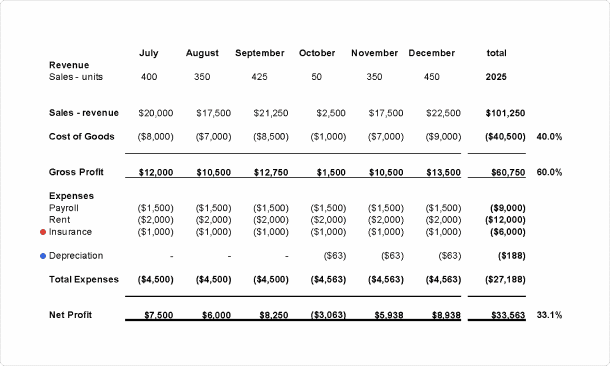

Example profit and loss

- The treatment of the Insurance as a monthly expense

- The Depreciation of the asset commencing in October

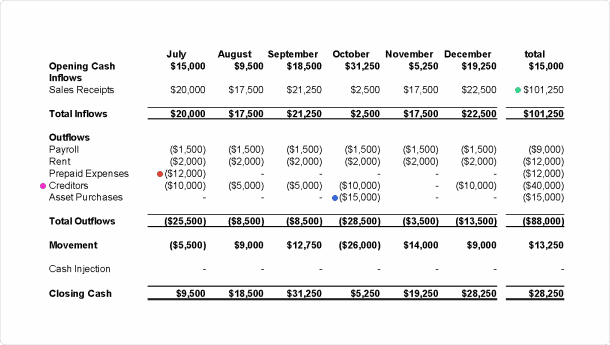

Scenario 1

All sales are paid for in the month they occur

- Sales Receipts are the same as Revenue as cash is received in the month of sale.

- The insurance expense is one cash outflow – Prepaid Expense.

- The Asset Purchase tool is one cash outflow.

- Instead of Cost of Goods Sold, we show our payments to Creditors for the inventory.

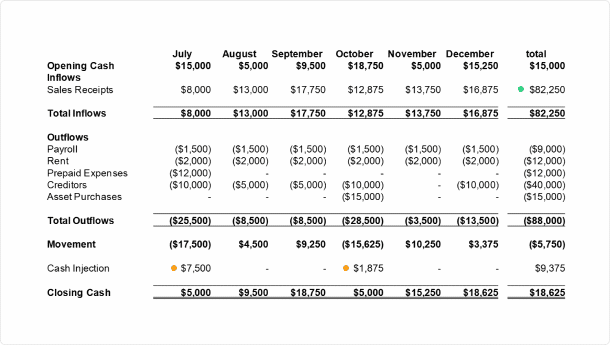

Scenario 2

60% of sales paid by end of month 1; 30% by the end of month 2; 10% by the end of month 3. A much more realistic scenario for most businesses!

There are two changes from Scenario 1:

- Sales Receipts have decreased each month

- In order to maintain our minimum (comfort level) cash balance, we had to inject $3,500 into the business

Scenario 3

40% sales paid by end of month 1; 30% end of month 2; 20% by the end of month 3; 10% end of month 4

- Sales Receipts have decreased further each month.

- In order to maintain our minimum (comfort level) cash balance, we had to make two cash injections into the business during the six-month period.

Is this a good enough picture of cash flow?

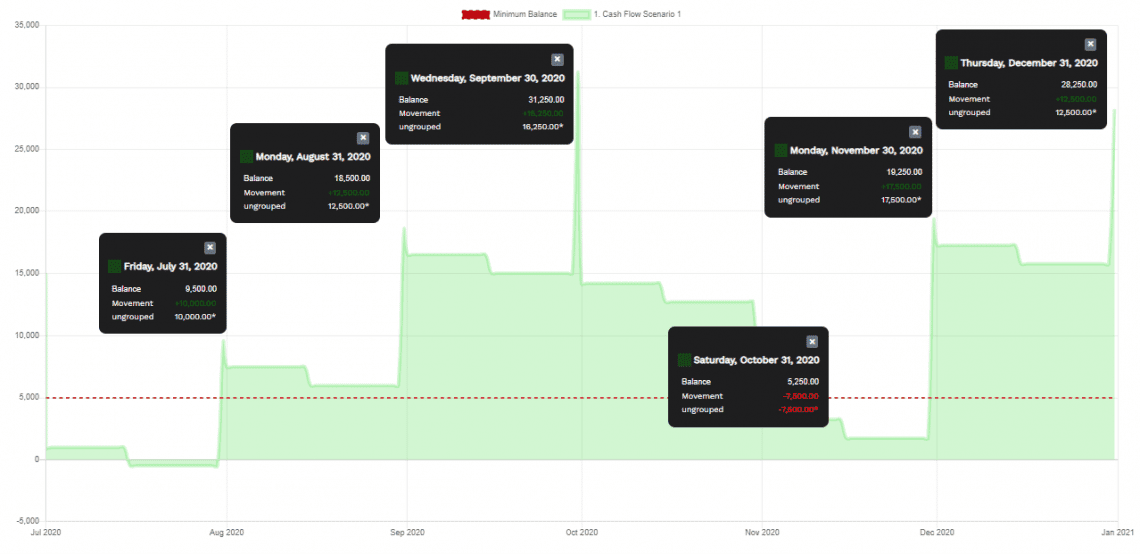

Looking at these cash flow scenarios a little deeper, we can see not enough detail is provided — we really need a daily analysis of forecast cash flow to be fully informed.

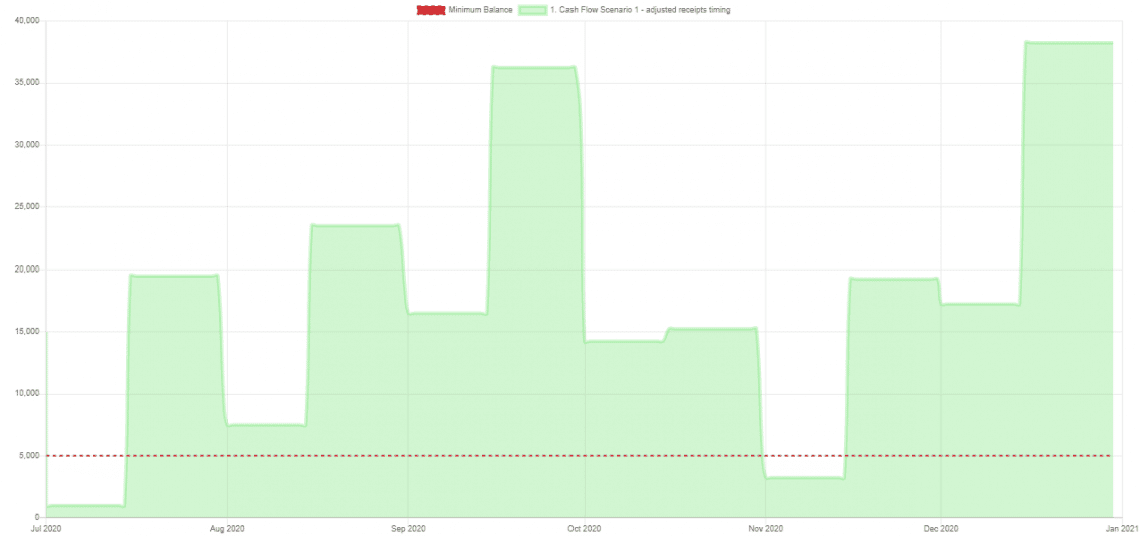

Look at Scenario 1 graphically, assuming all receipts are received on the last day of the month. There are two extended periods where we have breached our minimum cash level.

By taking a month-end view of cash flow only, we have no idea of the emergency that awaits us.

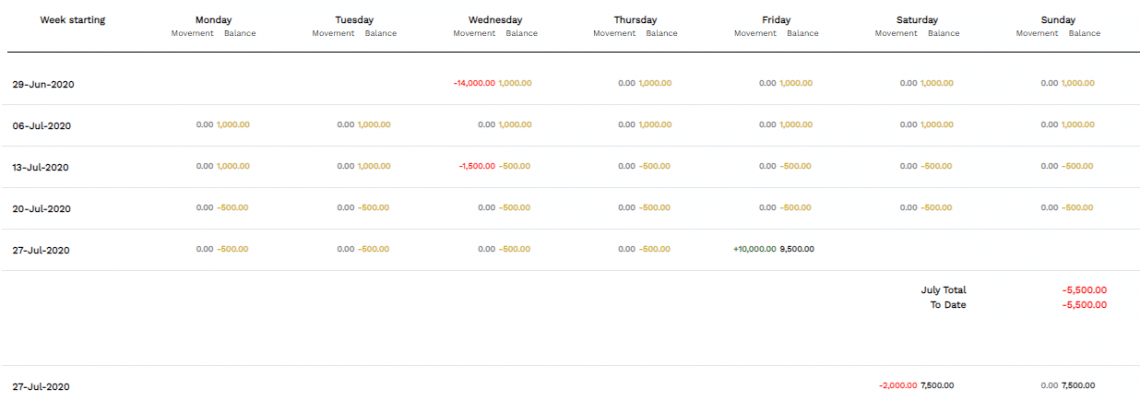

We get the same story numerically. We can see the insurance and rent payments on July 1 put our cash flow under pressure immediately — we don’t get that insight with the monthly summary.

Whichever way we look at it in detail, it’s clear a monthly forecast just isn’t enough, especially for a short-term view (up to 12 months).

However, assuming all cash receipts occur on the last day of the month is a little unrealistic. Let’s make a different assumption that payments are received mid-month and see what cash flow looks like now:

Now we can see if cash inflows were received regularly during the month, we wouldn’t breach our comfort level of cash.

Our cash outflows occur on set days each month, so we need to ensure we have cash available on those days to cover them. It’s the timing of the cash movements that we need to understand in order to see how our business is travelling.

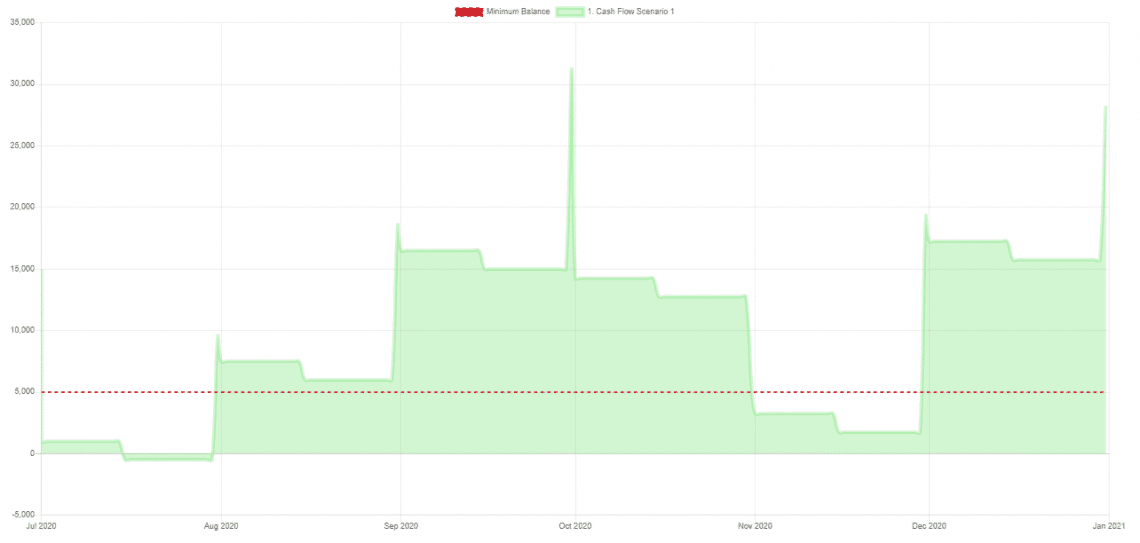

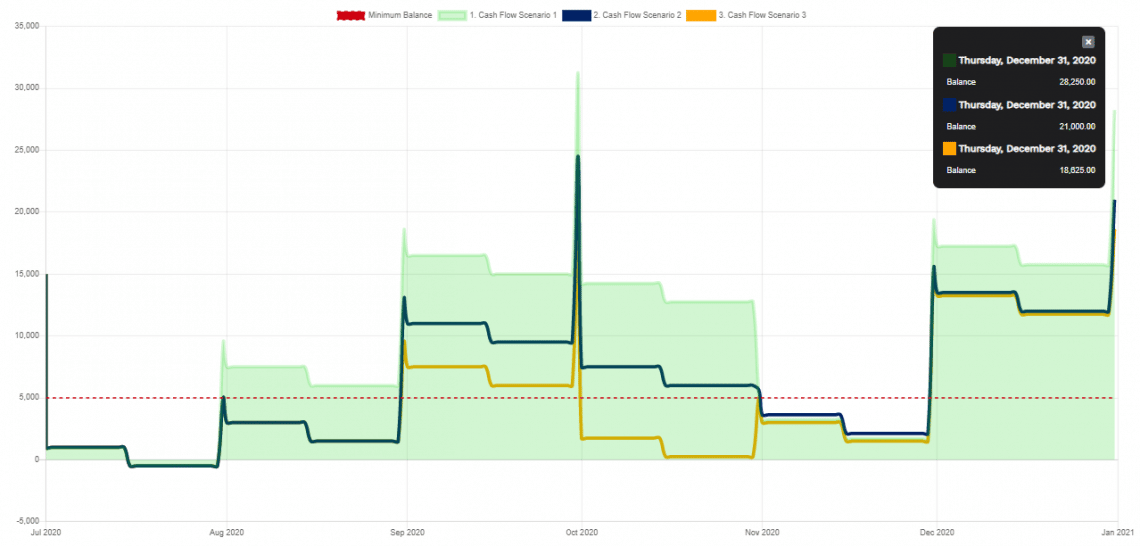

Let’s look at all three original scenarios at once:

The breaching of minimum cash is greater in Scenarios 2 and 3. Even though our initial model factored in cash injections so that the month-end cash balance was above $5,000, a more detailed look shows us that this may still not keep us out of trouble.

So you can see, the timing of your cash flows is crucial, as is the understanding of possible scenarios.

Conclusion

Cash flow forecasting is arguably the most important task in running a business. Any business — including yours! That’s why we’ve broken down cash flow budgeting, planning, and forecasting into a common-sense approach applicable to any business.